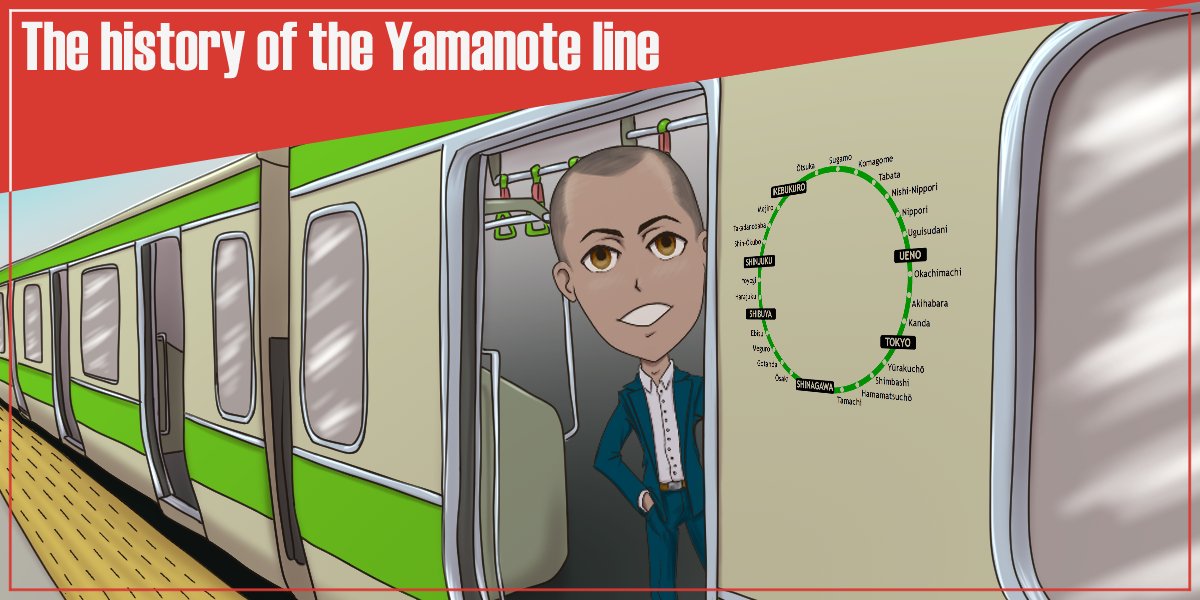

It’s no debate that Japan’s railway system is one of the best and most efficient in the world. If you’re a train otaku or interested in learning about how the Yamanote Line went from transporting mostly cargo and a few passengers, to now carrying over five millions passengers per day, do read on!

The history of the Yamanote Line has experienced assassinations, natural disasters, even a world war, and the way each station was rebuilt, some showcasing its original infrastructure, is a captivating read. Our host, Anthony, will tap the research and knowledge of Michael, who has featured the Yamanote Line’s history in his YouTube channel, Japanese History.

The initial purpose of the Yamanote Line was to move cargo

On Oct. 14, 1872, Japan’s first railway line, named Tokaido Line, would officially open – a 29-kilometer stretch connecting Shimbashi in Tokyo to the port city of Yokohama through Shinagawa. The line was born out of freight distribution, and passenger movement and flow weren’t even considered at that time. This stretch between Shimbashi and Shinagawa was ultimately the first bit of the Yamanote Line.

The second line, the Tohoku Line, came from the north of Japan. It was also used for freight distribution, namely silk and vegetables, manufactured or produced from the northern provinces. The line would stop at Ueno station, which would then be called the gateway to the north of Japan.

Connecting the north and south of Japan

When it comes to freight distribution, the most efficient and interconnected transportation system should be established. Japan soon discovered a missing link, a 5.5-kilometer section from Ueno in the north to Shinagawa in the south. However, in between that section, about a million people inhabited the area, making it a massive undertaking to connect the railway system’s northern and southern end.

So, in 1885, the Nippon Railway company opened a new private line (Shinagawa Line) through Tokyo’s virtually inhabited western land. It was almost quadruple in length than the 5.5-kilometer stretch, but the empty land made it faster to construct and cheaper to build. This stretch would eventually make way for Shibuya and its nearby stations.

50 passengers per day in Shinjuku?!

Here’s a mindboggling tidbit. When Shinjuku station first opened in 1885, it only catered to 50 passengers used the terminal each day. Today, Shinjuku is known as the busiest station in the world, seeing an average of 3.5 million passengers a day with 200 exits and 36 platforms. Don’t be surprised if you see north, south, east, and west all pointing in the same direction when reading the directions in Shinjuku station.

It should also be noted that the minuscule foot traffic of Shinjuku continued for a few decades. It was only after the 1923 earthquake where the eastern portion of Tokyo was devastated did the population make a move westward, thus boosting the roles of stations like Shinjuku and Shibuya.

Only two stations added since the full loop completion

The Yamanote Line full-circle loop was officially completed in 1925, with Okachimachi and Akihabara stations being the last two established. There were five train services offered per hour on the full-loop track. It took a train 72 minutes to complete the whole loop. After almost a century of operations, only two other stations were added to the full-circle loop, Nishi-Nippori and Takanawa Gateway, which opened last year.

Over half of the Yamanote Line devasted in World War 2

Yamanote Line was not spared from attacks during WW2. Ebisu, Gotanda, Osaki, Shinagawa, Yurakucho, Akihabara, Komagome, Sugamo, Ikebukuro, and Takadanobaba would all burn to the ground. Over half the train stations were damaged in some way or another. Harajuku’s iconic wooden station (already demolished in 2020) also got a direct hit attack, but the bomb turned out to be a dud, and the station was spared.

The jewel in Yamanote Line’s crown, Tokyo station, also suffered from multiple direct hits by bombs while the famous Marunouchi side building was destroyed by a fire. Although the Yamanote Line was severely damaged and operations were sporadically ceased, the entire loop continued amid quick restoration efforts.

Why many stations had a European theme

If you’re wondering why many of Japan’s earlier stations showcased European architecture with red bricks, wooden paneling, and arched ceilings, it’s because Japan commissioned German architect Franz Baltzer to design them. Baltzer was responsible for many of the train stations in Berlin, and he incorporated a similar approach in Japan.

However, when he later submitted his proposal for Tokyo station to the Japanese government, they were horrified by how he tried to fuse traditional Japanese architecture with Europe’s. Think extravagant castles meet minimalist temples. At this point in history, the government was focused on transforming Japanese society modeled on European and North American values.

The government then turned to Tatsuno Kingo, who was a Japanese architect passionate about Western design. He was tasked to make the foundation building long and spectacular. Needless to say, he didn’t disappoint. There are over 7.5 million locally manufactured red bricks in the crown jewel station, which cost about $650 million to create.

The future of the Yamanote Line

With the Yamanote Line reaching its full capacity in terms of the number of stations, the only direction now is for renovation and improvement. Take Shibuya station, for example, which is currently in the process of an upgrade. You can also expect that the design will be more user-friendly, especially to the aging population, so there will be more escalators, elevators, and wheelchair ramps.

Another reputation that precedes Japan’s railway system is its cleanliness and that the infrastructure works well 24/7. Over a century and a half into operations and the tracks are still functioning, and the overall system design is still intact. Furthermore, the cars might be old, but they remain clean.

According to Michael, the future for Yamanote Line and the entire railway system in Japan would be in the field of artificial intelligence and autonomous technology. JR East has communicated that about 25 percent of its workforce, or 10,000 staff members, are expected to retire in the next ten years.

In 2019, there was a driverless test in the Yamanote Line to test and debug this technology. There are a few issues to be ironed out, such as the train pulling up unaligned to the platform by several meters. The introduction of this driverless technology has not been announced, although it’s not expected within the next ten years.

The stations, as well, will be less and less staffed. For example, the Takanawa Gateway station is somewhat a prototype indicating an automated station. You will notice cleaning robots tirelessly sweeping the floor, information robots offering guidance in multiple languages, and security robots on standby for emergency assistance.

From a shack on the side of the road used as a loading bay for goods to a city within a city equipped with robots understanding your inquiry in your native language, it’s no doubt the journey of the Yamanote Line was an exciting one. Today, it is the heart and lifeblood of Tokyo.